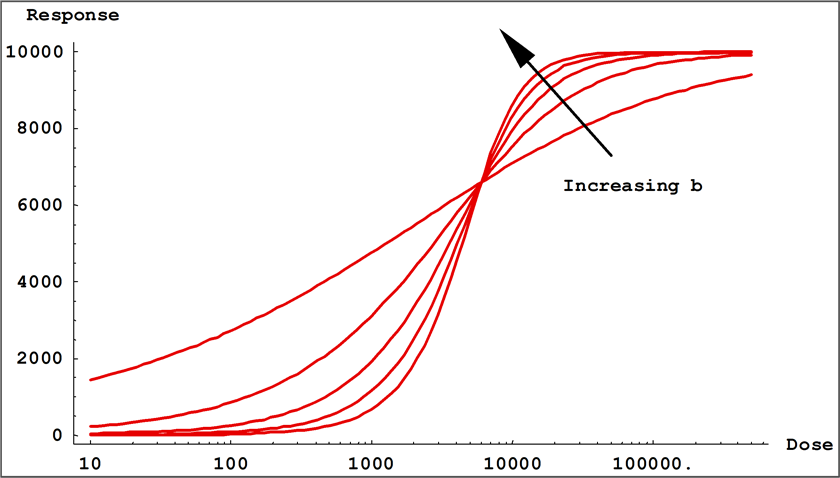

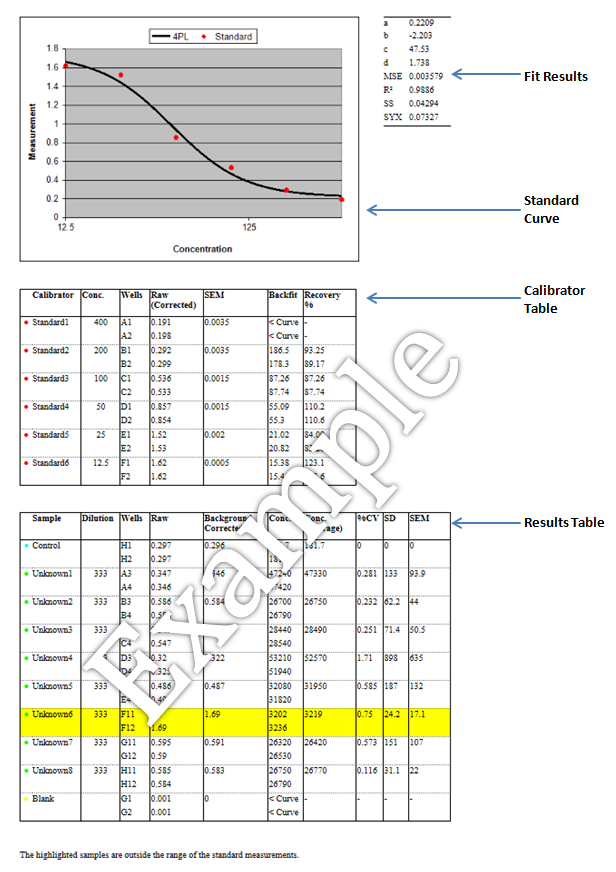

Samples outside the range of the determined a and d cannot be calculated. The curve can only be used to calculate concentrations for signals within a and d. Note that the a and d values might be flipped, however, a and d will always define the upper and lower asymptotes (horizontals) of the curve. this is related to the steepness of the curve at point c). the point on the S shaped curve halfway between a and d)ī = Hill’s slope of the curve (i.e. what happens at infinite dose)Ĭ = the point of inflection (i.e. what happens at 0 dose)ĭ = the maximum value that can be obtained (i.e. The 4 estimated parameters consist of the following:Ī = the minimum value that can be obtained (i.e. Of course x = the independent variable and y = the dependent variable just as in the linear model above. The model fits data that makes a sort of S shaped curve.

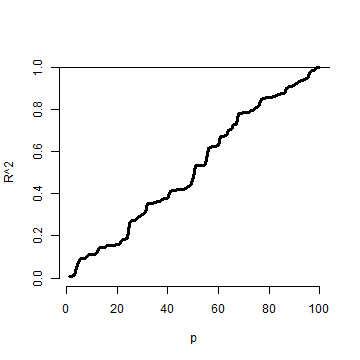

As the name implies, it has 4 parameters that need to be estimated in order to “fit the curve”. It is quite useful for dose response and/or receptor-ligand binding assays, or other similar types of assays. This model is known as the 4 parameter logistic regression (4PL). This leads us to another model of higher complexity that is more suitable for many biologic systems. The bad news is that linear regression is seldom a good model for biological systems. The good news is that linear regression is pretty easy. The smaller the SSq, the closer the observed values are to the predicted, the better the model predicts your data. This is known as the sum of squares (SSq). To get around this you should square each of the residuals, which render all the values positive, then sum them. Summing these is not very useful, as even a random set of data points may generate residuals that sum close to zero. However, since some observed values will likely be above the fitted curve and some below you will get positive and negative residuals. The smaller the sum the better the data fit the predicted curve. To check the predicted fit of the line one usually calculates all the residuals (observed – predicted) and sums all the differences. your data) and the predicted values (i.e. The goal is to determine values of m and c which minimize the differences (residuals) between the observed values (i.e. If you have made it past algebra in school you have most likely encountered this model.

what you control, such as, dose, concentration, etc.) To start let’s look at the simplest model, known as a linear regression: For now, I will talk about two models: Linear Regression

FOUR PARAMETER LOGISTIC REGRESSION WITH POLYMATH SOFTWARE HOW TO

Let’s look at a simple model to discuss how to “fit” a curve and a more complex, “biologically relevant” model to start applying what we know.Ĭhoosing a model really depends on a thorough understanding of what it is that you are measuring (see How to Choose and Optimize ELISA Reagents and Procedures). Once the standard curve is generated it is relatively easy to see where on the curve your sample lies and interpolate a value. You can think of the standard curve as the ideal data for your assay. This set of data for the standards allows one to “fit” a statistical model and generate a predicted standard curve. The standards, in your assay, should be tested at a range of concentrations that yields results from essentially undetectable to maximum signal. In order to determine a quantity of something you will need to compare your sample results to those of a set of standards of known quantities. This is where things can get interesting. You’ll probably want to also determine the quantity of the material you have detected.

Maybe you will even develop your own assay. All you have to do is test the sample using any number of commercially available kits. You have been asked to perform an ELISA to detect a molecule in a biologic matrix.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)